Why I Trained Indoors for the Atlas Mountain Race

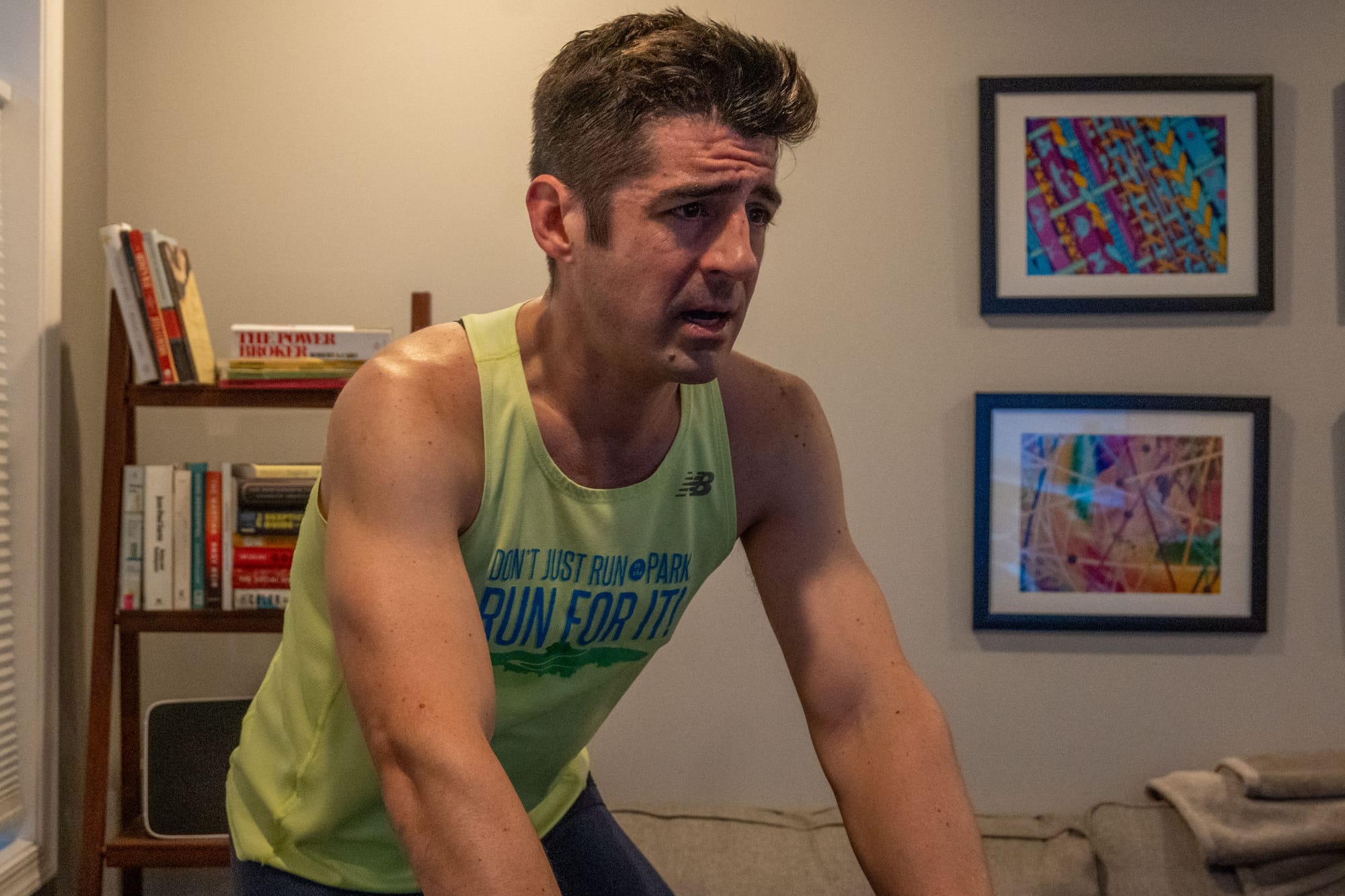

Nick Marzano trained primarily inside his South Philly rowhome in preparation for Morocco's Atlas Mountain Race. His journey is surprising, deeply personal, and heroic all at once.

The Atlas Mountain Race cuts an 800-mile crescent path, clockwise from landlocked Marrakech back around to Essaouira on the coast. Picture twelve o’clock to ten o’clock, but bumpier. Starting in the late evening, riders head straight for the biggest climb of the route, Mt Telouet, at 8,500 feet. Most will make the summit in the smallest hours of the morning. From there, the route bends south, winding through the floors and ridges of the Anti-Atlas before curving West to the shore.

Every so often you’ll be treated to a stretch of fresh pavement. More frequently, you’ll find your hands locked on the brake levers as you guide your mechanical beast down a precarious mule track. Or you will teeter on your pedals as you slowly fumble up an old colonial piste made of brick and boulders and gaping holes.

When you think you have seen the worst of it, and need only trace the low, easy shoreline north to Essaouira, you will allow yourself to get lost in thoughts, with one hand on your drop bars and a pack of crème cookies in the other, and the pavement will end abruptly in a pit of sand, and you will fly over your handlebars in front of a curious Moroccan family, and they will exert great restraint suppressing their laughter. Then you will push your bike through seven miles of burnt orange dunes. You will sleep one last time by the side of the trail, wearing your helmet as a pillow, and wake shivering under the empty desert sky.

You will pass goats. Camels. Kind locals. Curious children. Calls to prayer. Full lives you can’t know. Burgundy sunsets. Frigid, blank nights. The race will erode your body, and it will change your life.

So why would I train for the February 2023 edition of the Atlas Mountain Race almost exclusively from the climate-controlled confines of my South Philly row home? Isn’t it a bit dangerous, you might ask, to never--not even once--test my fully-laden rig on a shakeout weekend in the wilderness? Irresponsible even? Lazy?

In the interest of building a little credibility, I can share that I did finish the event, placing 44th place out of 197 starting riders. Far from the pointy end to be sure, but in a race where roughly forty percent of riders end up dropping out before they reach Essaouira, one could do worse.

With that modicum of authority established, here then was my rationale for training indoors:

It was more efficient. From my home in Point Breeze it takes some ten miles to reach the hills of Manayunk or further suburbs of Philadelphia. This extended warmup passes stoplights, reckless drivers, and meandering pedestrians. Add to this the time required to bundle up, pump tires, check lights, and so on. On the smart trainer, I could be out of bed and onto a 3,000-foot climb in a mere ten minutes.

Trainer workouts are more consistent. Trying to pull off high-intensity intervals in the city with any consistency takes planning, luck, and lots of hill repeats. By contrast, my training plan was designed by a coach from out west. It assumed access to the long, steady climbs of the Rockies. With pre-programmed and custom workouts on my smart trainer I never had to worry about efforts stopped short by a red light, or a climb physically ending just as my heart rate got going. You can find plenty of elevation around Philly, but timing sustained efforts might mean spending a morning going up and down the Wall. So, I traded outdoor monotony for indoor monotony.

It was winter. The Atlas Mountain Race takes place the first week of February, meaning training should begin somewhere in the fall. On the bright side, this means most folks will have a pretty good base. However, the timing is such that training volume should ramp up significantly heading into the holidays, peaking in late January when daylight is scarce. I do not mind a dark forest—I have seen more than a few suns rise on an all-night effort. I am less fond of dark, salted city streets.

I felt like I had already tested my limits. Nights in the desert will easily drop below freezing, and would-be racers would do well to test their equipment and their resolve through exposure training. Personally, I felt like I had enough exposure for one year. The prior summer I had raced the Tour Divide from Banff to the Mexican border. In the north, unseasonably deep snow blanketed the mountains from Canada through Montana. I post-holed for hours through passes that otherwise take sixty minutes to ride. Toward the south, early monsoons doused the New Mexico portion of the track for days. I knew how to manage sweat in the cold, stay dry in a daylong downpour, and push through the fear of a chasing electric storm. That time, I finished 22nd in a field of over 200. Why not give myself a little credit and focus purely on fitness this time?

I was feeling a little burnt out and lazy. Ok, sure, you got me. If I’m honest, I did it as much for the convenience and comfort. Did I binge two seasons of Somebody, Somewhere on HBO Max during 8-hour rides in my living room? Yes I did. Did I cry profusely at the main character’s quiet pain, a result of her self-inflicted isolation, and then again at her inevitable growth and redemption through the love and forgiveness of her found community of misfits and family? Several times. Real food and a warm bathroom were always just a pause button away.

Also, I was a bit depressed. Well, hold on. No... I don’t know about that. I couldn’t have been depressed. I was having a banner year. I’d completed a 2700-mile race of a lifetime. I’d met dozens of new friends through biking and bikepacking. Weekdays I would log on to fulfilling work, supporting clinicians who had been on the frontlines of the pandemic. My boss and coworkers were supportive of my taking time for not one, but two global races.

Plus… plus! My divorce was nearly finalized after a hard year and a half of lawyers, curt text messages, and grieving the death of an imagined future. I’m pretty sure I was moving past the worry at all that I would never be a father or, at least, anything but an old father. I was even pretty close to trusting myself that I made the right choice by asking for the separation in the first place. And, I promise my therapist would tell you, I was really just a hair away from forgiving myself!

I was hiding from the end of my marriage. FINE. YES. Fine. It’s fine. I was scared. Of the future. Of the Final Decree that would show up in my mailbox any day now with the official court seal. Of becoming untethered and set adrift from a narrative. Of the scattering of life pages, out of order, missing whole sections of myself. I was scared to step out onto my street and catch an awkward look or scowl from the neighbors. My wife and I used to wave to them, have stoop beers with them, get packages for them, weed easements with them, and plan summer block parties with them. I had ended things. They quietly took me off the group chat. I suspected they didn’t think it was fair to her. It felt futile and crass to explain, to plead a case. That I had tried, asked for the therapy, voiced hurt, felt hopeless. Close friends knew the details, loved us both. Love us both still. Want us to be loved. So, yes, I was scared of what I had lost, what I may have become, and what I might not ever be. And I stayed inside.

I had called a Lyft to the Philadelphia Airport when I remembered to check my mail one last time. There it was, a large rectangular envelope signifying the legal end of a type of life. I opened it, ran upstairs to quickly scan it before the car arrived, and emailed a copy to my ex-wife and our lawyers. A car horn. After twenty-four hours of transport I was thrust into the buzz and smoke and mad movement of Marrakech.

I bartered with a cabby who agreed to hang my bike box out of his small hatchback. We sped to the Mogadir Kasbah, a hotel fifteen minutes beyond the walled Medina. There I met Molly, and Chris, and race director, Nelson. I reconnected with Allan, whom I’d met on the Tour Divide, who in turn introduced me to Chas and Alvin. In an alleyway tucked behind the souks, Zeno, Floyd, and I found a tanjia stall, where slow-cooked beef tumbled out of clay jars onto tables lined with parchment paper. We joked and talked straight about our hopes, our fears, our demons, and our bikes.

On the first night of the race, around two-thirty in the morning, I reached the peak of Mt. Telouet. It had snowed at altitude just days prior, and the moon lit the white tops of the surrounding sister peaks. Below I could see the other riders, a twisting rope of headlights, winding around the switchbacks I had come up. The climb had spread us out, but here we all were: strung together, carrying what we could manage to carry, braving this dark night for the promise and hope of warmer days ahead.

I trained inside because--in that time and in that place--it was what I needed to do to make it to the other side. To see a terracotta sun rise again over the wide horizon of the earth.